Harry Fonseca: Coyote Is

“I first portrayed Coyote in a traditional way. A stuffed coyote head, a cape that covers the body, two sticks held in the hands to symbolize the Coyote’s front legs—that’s how the Coyote is portrayed in the dance. That’s how I painted Coyote, originally.

But the more I got into him, the more I realized he was a contemporary figure. Stardom, frills, the Country Club, the American stereotype of a beautiful woman: if it glitters at all, it possesses Coyote. Even aluminum foil and paper sparkles will take him over. “I want! I want!" he will say.

So I began to put him in contemporary settings. He’s still totally unpredictable. In mirrored sunglasses and a full headdress he does a war-dance on a busy city street. On a dance floor, he croons louder than anyone, dips and sways more flamboyantly.

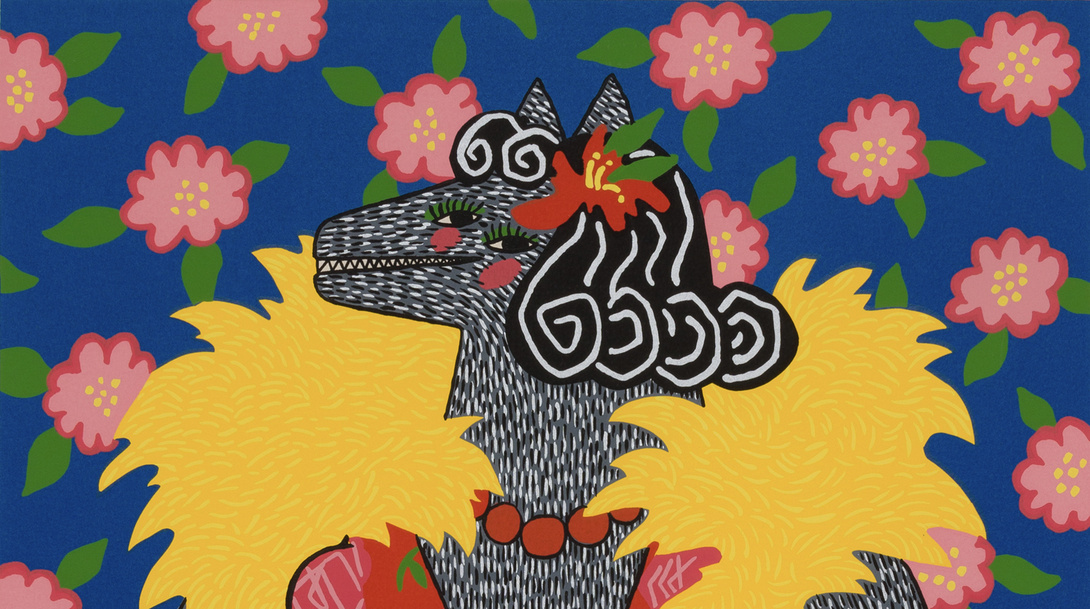

Rose...is a very new character… a female coyote adds a whole new dynamic to what I’m doing. I’m just beginning to explore the possibilities: lipstick on her lips around her sharp, coyote teeth, makeup on her snout, party dresses with slits. I’ve just done a nude of Rose rising out of the sea, covering herself modestly. The whole stereotyped idea of what femininity is—it aligns perfectly with a part of Rose’s nature.

The Coyote is always totally impulsive and very powerful. He’s not always the ‘good guy’ either. I became fascinated with the Coyote and from then to now, the more I learned about him, the more I got into him—or the more he got into me.

The Coyote is the traditional Maidu trickster. He’s impossible to pin down. He’s total animalism sometimes. He can be human, sympathetic, giving. He’s an authentic wizard, a cheap-shot magician. He can kill a child one minute and lead a whole people to safety the next. A vagabond today, married to the chief’s daughter tomorrow. He’s acknowledged as both the bringer of life and the bringer of death. That says it. He’s a heavy character.”

—Harry Fonseca to Artists of the Sun, 8/20/1981

Harry Fonseca (Nisenan Maidu/Portuguese/Hawaiian, 1946-2006) was born and raised in Sacramento and was an enrolled citizen of the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians. He was influenced by the Maidu origin stories told to him by his uncle, Henry Azbill. In 1990, he moved to Santa Fe, where he lived until his death in 2006. He exhibited widely and had a number of exhibitions at LewAllen Contemporary and Elaine Horwitch Galleries. He participated in We the People, an exhibition curated by Jimmie Durham and critic Jean Fisher in 1987 at Artists Space in New York.

His retrospective Harry Fonseca: Coyote, A Myth in the Making, curated by Margaret Archuleta, traveled across the United States (1988-1989) including the Museum of Natural History, Los Angeles, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C, Joslyn Art Museum, and Oakland Museum of California, amongst others. In 1999 he was a featured artist in Ceremonial at the Venice Biennale curated by the Native American Arts Alliance, and has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of the Plains Indian (1976), The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian (1983 & 1996), Southwest Museum (1989), Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History (1990), the Crocker Museum (1992), The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian (1996), the Oakland Museum of California (1998), The National Museum of the American Indian (2003), Institute of American Indian Arts Museum (2004), Emmanuel Gallery (2006), the Eiteljorg Museum (2018), amongst others. Most recently, his work was a part of the exhibition When Coyote Leaves the Res at the Autry Museum of the American West (2019).

This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Margaret Archuleta (Tewa/Hispanic, 1950-2023). Margaret was a curator, scholar, and a friend of Harry Fonseca. She was a beloved figure within the field of contemporary Native Art.

Harry Fonseca, Coyote Woman, 1979. Lithograph. 33 x 25 1/4 inches, framed; 28 1/4 x 20 inches, unframed; Edition of 150.

Harry Fonseca, Coyote Koshare Sitting with Melon, 1984. Graphite and color pencil on paper. 33 x 25 1/4 inches, framed.

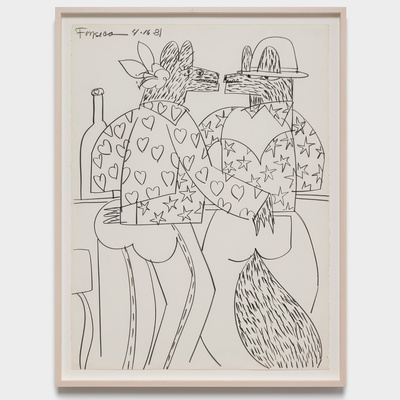

Harry Fonseca, Pow-Wow Club, 1981. Graphite on paper. 29 1/8 x 22 1/8 inches, unframed; 33 x 25 1/4 inches, framed.

Harry Fonseca, Rose on the Half Shell III, 1988. Acrylic on paper, framed. 33 x 25 1/4 inches, framed.

Harry Fonseca, Coyote and Turtle, ca. 1982. Pastel on paper. 29 x 21 inches, unframed; 33 x 23 1/4 inches, framed.

Harry Fonseca, Shuffle Off to Buffalo, 1983-84. Color lithograph with glitter. 36 x 26 7/8 inches; Edition of 75.

Harry Fonseca, California Bear Dance, 1979. Serigraph in colors on paper. 33 x 25 1/4 inches; Edition of 50.